Welcome back to the China House Brief.

Last Friday (4 July) marked the one-year anniversary of the Labour Government’s landslide victory in the 2024 General Election. It would be fair to say it has been a challenging 12 months for the Government – particularly on the domestic front. Deep-rooted structural issues, a deeply hostile media, and an increasingly restive population – impatient for real change – have made for a steep learning curve for the Party.

While some of the criticism of the Government’s domestic agenda has been unfair – not least because much of it has been coming from those directly involved in causing the problems the country is currently facing – it would be fair to say they have not gone as far, or as fast, as they might in tackling problems head-on.

There are also lingering doubts around certain appointments and key personnel. After Sue Gray’s unceremonious departure last year, on Saturday (5 July) The Guardian reported that Number 10 “regrets choice of ‘insipid’ new Cabinet Secretary [Sir Chris Wormald]” amid suggestions he is “prone to wringing his hands about problems rather than coming up with solutions, and too entrenched in the status quo” [The Editor: Back in December, we wrote of the appointment: “as Sir Chris takes the helm, one wonders whether his decades of navigating the corridors of power have adequately prepared him for the task of rewiring them – or if, in true Sir Humphrey style, the wires will simply be neatly relabelled and left exactly where they are”].

Since coming to power, Government Ministers have frequently invoked memories of Clement Attlee’s transformative post-war Labour Government (1945–1951). At the time, the UK was exhausted and economically devastated – rationing, housing shortages, huge debt, and a crumbling empire.

A series of economic crises, early in Attlee’s tenure – including the convertibility crisis of 1947 and the devaluation of the pound in 1949 – combined with austerity and rationing, which continued post-war, led to discontent. Despite these challenges, Attlee successfully established the welfare state: NHS (1948), national insurance, and nationalisation of key industries. Ironically, Labour subsequently lost the next General Election in 1951 but left a lasting institutional legacy.

The UK under Attlee also became the first major Western country to recognise the People’s Republic of China, on 6 January 1950. The UK was motivated by practical interests, including the protection of its colonial holdings in Hong Kong, and the desire to maintain diplomatic and trade links with the new regime.

For the current Labour Government, the Financial Times’ Martin Wolf summarises the issue: “The UK suffers from three failures: failing politics; a failing state; and a failing economy. Of these, the last is much the most important… [and] the state is… unable to ameliorate the painful trade-offs this reality has imposed… [In this context] it is crucial to recognise the political responses we have been seeing since 2010. By and large, these have fallen into two categories: charlatanism and timidity. The charlatans pretend that something simple – Brexit or huge unfunded tax cuts – will deliver. The timid have been relatively responsible. But they have been unwilling to admit the scale of the economic and political challenges they confront and then make hard choices. Keir Starmer is not a charlatan. But he has not been prepared to take on the burden of leadership that current conditions require”.

The recent U-turn on benefits cuts was just the latest example of a Party that continues to duck the most difficult trade-offs.

Bloomberg’s Adrian Woolridge was more scathing in a recent piece on the causes of the UK’s failure to produce “a competent ruling class”:

“The British civil service, once widely regarded as a Rolls-Royce, is now a sputtering Trabant. The decline of the Foreign Office is so pronounced that a recent ambassador to France struggled to speak the local language… The old systems of elite formation have been allowed to crumble. The trade unions once provided formal education as well as day-to-day training for such Labour giants as Ernest Bevin and Nye Bevan. Now they are a shadow of their former selves. Oxford University emphasized the study of political history in both its Modern History course and in the politics part of PPE (Politics, Philosophy and Economics). Now the history course puts less emphasis on the study of political, administrative and constitutional history than in the past, and the politics course focuses more on theory than on practice [The Editor: The author studied Modern History at Balliol College and Philosophy at All Souls College, University of Oxford]. The civil service had an elite national training college at Sunningdale. [This] was closed in 2010 as part of broader cost-saving measures. Various attempts to update the system have proved disappointing. The new Blavatnik School of Government at Oxford, which was supposed to be a British equivalent of Harvard’s Kennedy School, draws 80% or more of its students from abroad. Dominic Cummings’ attempt, while serving as Boris Johnson’s chief adviser, to modernise central government by shock therapy ended up discrediting sensible ideas, much like Elon Musk’s DOGE in the US”.

Woolridge rightly highlights the corrosive effects of the Westminster Bubble and political commentariat:

“Since the turn of the century, the British governing class has responded to change not by directing it to creative purposes but by being carried along by it. Politicians waste time responding to an ever more frantic news cycle: Special advisers are increasingly in the business of managing the news rather than shaping policy. Political journalists are more like sports reporters – who’s winning the race to the top, or who’s falling behind – rather than serious observers of statecraft. There is no time for serious reflection or planning… There is only short-term management of chaos”.

The embarrassing, hyperbolic reaction to the Chancellor’s tears in the Commons over a “personal issue” last week was yet another low from a political commentariat hooked on psychodrama, manufactured crises and opinion-driven fluff. Their continued inability – or unwillingness – to focus on substance continues to critically undermine public discourse around politics and only hastens a return to the damaging populism of Brexit and Johnson. Inevitably, Nigel Farage’s Reform UK are currently surging in the polls, despite their own internal strife and scandals.

As Steve Bannon told the Financial Times last week (4 July): “Populism is the future of politics”. It is hard to disagree with this assessment – just as it hard to understate the role of the low-effort click-chasing political commentariat and unregulated social media in bringing this about.

Curiously, Woolridge places the blame for the failure to make the necessary reforms squarely on the shoulders of the Labour Party – rather than any of the five Conservative Prime Ministers that led the country had in the intervening period:

“The most successful reforms of government have all come from the top down… The British government has unfortunately missed two recent opportunities to engage in such comprehensive reforms – the Blair landslide in 1997 and Starmer’s in 2024 – and is instead stuck in a doom loop: The more short-term problems multiply, the worse the government of the country becomes. And the worse the government of the country becomes, the more crises multiply”.

However, with the Prime Minister’s personal approval ratings now at record lows, ironically, this may embolden him to do what is necessary, rather than merely what is popular or politically expedient.

In contrast, on the international front, the Government – and the Prime Minister, in particular – have demonstrated an energy, level of focus and deftness-of-touch that has been largely missing from UK foreign policy for many years.

On China there have been signs of a more consistent, measured approach to engagement – what has been missing is a clear articulation of the Government’s overarching approach.

The Labour Manifesto, on which the Party won their landslide victory, contained only two fleeting references to China – promising to “bring a long-term and strategic approach to managing our relations” and “improve the UK’s capability to understand and respond to the challenges and opportunities China poses through an audit of our bilateral relationship”.

It was hoped the China Audit would provide this articulation and, for months, Government Ministers hinted it would be the answer to any-and-all questions about the UK’s approach to China – including the difficult trade-offs involved.

As the months passed, timelines began to imperceptibly slip. Back in November 2024, during a debate on Taiwan, Indo-Pacific Minister Catherine West assured Parliamentarians the Audit would be “ready for public discussion in spring 2025”.

By March, West was promising “the audit will be made public before the end of the spring”. By the end of April, West stated the Government had “never committed to a specific date” and that the process would be concluded “in due course”.

The same month, in response to a potentially tricky question from former Security Minster Tom Tugendhat about China – with respect to critical minerals and forced labour in green energy supply chains – West sidestepped and suggested “all will be revealed when the China audit comes forward with the specifics on his question”. By the end of the month, that commitment had been watered-down somewhat – only promising to “share elements of the Audit publicly” with other parts remaining “confidential, in order not to compromise UK interests”.

Three weeks after the end of meteorological spring (31 May) and three days after the end of the UK’s astronomical spring (21 June), it seemed the wait was finally over as the Foreign Secretary stood up in the House to deliver his statement on the China Audit.

In this issue of the China House Brief we will be unpacking the Foreign Secretary’s statement on the fate of the China Audit – and what it tells us about the state of his beleaguered department. The Government said the Audit informed the Strategic Defence Review, which we explored in the last issue, as well as the new Industrial Strategy, National Security Strategy, and Trade Strategy. We’ve combed through all 300+ pages of these documents, so you don’t have to, in order to do what the China Audit (spoiler alert) failed to do – explain where the UK Government is heading on China. We also take a look back at the last time a Labour government released a China strategy, revisit the China ties of two former Conservative Prime Ministers, and check in on what “Daddy” has been up to.

This will be the last issue of the main brief before we head off on the China House Brief-equivalent of an imperial summer retreat – escaping the stifling summer heat of the capital and retreating to cooler, more scenic locales, be it the Summer Palace (颐和园), Chengde Mountain Resort (避暑山庄) or Beidaihe (北戴河).

If you want to stay abreast of all things UK-China during the balmy summer months, why not consider becoming a Plenipotentiary Ambassador to get our exclusive monthly brief, The Rebrief, as well as full access to our archives – all for less than the cost of a single London pint. The next issue of The Rebrief drops on 31 July – upgrade now to stay fully briefed this summer.

Without further ado, let’s get started.

Four Strategies and an Audit

June marked the peak of Whitehall’s annual “strategy season” with four major new strategies with implications for UK-China relations published in quick succession. First out the gates was the Strategic Defence Review – covered in our previous issue – which has been quickly followed by the Government’s new Industrial Strategy, Trade Strategy and National Security Strategy.

Amid this flurry of high-profile launches, the Foreign Office quietly released the bare minimum on the long-awaited China Audit – the implications of which we will explore in the final part of this section.

The Industrial Strategy

The UK’s new ‘Modern Industrial Strategy’, originally announced last autumn, was published on 23 June 2025. It aims to provide a long-term, whole-of-government approach to driving economic growth – particularly in eight high-growth sectors, referred to as the “IS-8”.

The IS-8 also get their own Sector Plan – each of which are 70-90 pages long, and substantive pieces of work in their own right:

Advanced Manufacturing (6 mentions of China)

Digital and Technology (6 mentions)

Creative Industries (5 mentions)

Clean Energy Industries (2 mentions)

Professional and Business Services (0 mentions)

Defence (not yet published)

Life Sciences (not yet published)

Financial Services (not yet published)

Central to the Industrial Strategy is the partnership between government and business, designed to provide the strategic certainty required for increased public and private investment. For its part, the Government has pledged to improve infrastructure and planning, tackle high electricity costs, reform regulation, boost R&D, and align education and immigration systems with future labour market needs.

Through increased business investment, the Government hopes to enhance UK productivity, while ensuring the benefits of growth are shared across regions, particularly through targeted support for city regions and IS-8 industry clusters.

As we’ve highlighted previously, Automotive is a strategically important sector for the UK. Unsurprisingly, it features prominently in the Advanced Manufacturing Sector Plan with the Government aiming to build on the UK’s “record of innovation in propulsion, energy systems, and driverless technologies” in order to give the UK “a competitive edge in the transition to Zero Emission Vehicles (ZEV) and Connected and Autonomous Mobility (CAM)”.

As if to highlight the challenges that lay ahead for the sector – and the Government – a few days after the publication of the Industrial Strategy the Financial Times reported that British sports car-maker Lotus plans to end production in the UK, putting 1,300 jobs at risk. Lotus has been majority-owned by Chinese firm Geely since 2017.

From a UK–China perspective, the Industrial Strategy acknowledges the shifting global landscape, in which economic security and resilience are now seen as important as openness and free trade - reflecting the Chancellor’s Securonomics framework [The Editor: On Tuesday (8 July), the Government also published it’s new Resilience Action Plan, which is primarily focused on domestic preparedness].

In the Upside Down Era® “an activist government working alongside business to project our national interests and promote the international architecture underpinning them will only be more critical… Government must be pragmatic, agile, and smart in navigating this environment. We will engage strategically with a wide range of partners… building resilience through cooperation and being assertive about our own interests and the importance of a rules-based international system… We have showcased this approach through our new deals with the US, EU, India… And we have stepped up political engagement with China, including through the Economic and Financial Dialogue, recognising the importance of maintaining a stable and balanced relationship that works in our national interest for resilient growth”.

The Industrial Strategy also underlines the importance of strengthening supply chain resilience and collaborating with trusted international partners in critical sectors – implicitly referencing concerns around overdependence on China in areas such as clean energy technologies, rare earths, and other strategic inputs.

We have explored the importance of industrial strategy – and the role of a more interventionist state – in dealing with increased geopolitical uncertainty in previous issues of the China House Brief, therefore we will next turn our attention to another key pillar of the UK-China relationship – trade.

The Trade Strategy

The UK’s new Trade Strategy, published on 26 June, aims to harness trade as a driver of sustainable growth, productivity, and job creation – building on the UK’s strengths, as an “open trading nation”. It is, in our view, probably the most interesting of the four strategies from a foreign policy perspective. The same day, the Government also published their latest Global Trade Outlook.

In an interview with the Financial Times, prior to publication, Trade Minister Douglas Alexander outlined the Government’s overarching approach: “Our strategic response to this new world can’t be based on nostalgia or post imperial delusion, let alone any ideological or dogmatic attachment to one trading bloc or another”.

The Ministerial foreword recognises the fragmentation of the ‘rules based international system’, recalibrating the UK’s approach around ‘three poles’ – US, EU and China:

“A generation ago, a survey of the outlook for trade might have begun with multilateral bodies, such as the World Trade Organization… But we need to start with realities of the changed world we are dealing with today – no longer a planet of ever-deepening integration, but a newly fractured globe, defined by rival power centres. We must not be naive about the reality that decisions taken in Brussels, Washington and Beijing will be based on their interests, not ours. However, we reject the notion that we must choose between the world’s ‘big three’ economies… There can be no place for the notion that the UK alone can reshape the global order. Instead, we must deploy clear-eyed pragmatism in support of our own businesses… This starts with a plan for realistic hard-headed economic diplomacy with each of those three economic giants”.

There will be a renewed focus on tackling “behind the border” regulatory barriers to consolidate the UK’s position as a global services ‘superpower’, with exports worth over £500bn last year. The Strategy announced the creation of a “Ricardo Fund” to help remove trade barriers abroad.

Regulatory complexity, non-tariff barriers, and market access restrictions continue to pose significant challenges for UK businesses operating in China. However, China remains one of the few markets where sustained government-to-government engagement and strategic lobbying can directly influence the commercial environment and unlock new opportunities for British firms.

Alexander insisted the UK would take a pragmatic approach to trade, continuing to build commercial ties with China, despite US concerns. The Minister dismissed any suggestion that the US has a ‘veto’ over UK decision-making, despite loosely-worded provisions in the UK-US Economic Prosperity Deal targeted at China: “We remain and will remain a sovereign actor on trade policy… We take seriously our responsibility on issues like investment security and economic security, but those decisions will be taken in London”.

In the Trade Strategy, the Government recognises that traditional Free Trade Agreements remain important, but also emphasises more nimble, sector-specific arrangements and digital trade protocols as faster routes to boosting exports and economic resilience [The Editor: In the very first issue of the China House Brief we said: “While it is unlikely we will ever see a UK-China FTA some form of ‘standalone’ agreement may be a possibility. The explicit focus on service exports would certainly suggest an agreement on financial services – of which the UK is the world's largest net exporter – seems a good bet”].

“Whilst there is certainly a place for FTAs with strategic partners, such as the landmark agreement reached with India, FTAs are only one of a range of possible tools with which to facilitate trade… There is a whole spectrum of bilateral and multi-party deals that can support trade but are less time consuming to agree than full FTAs… gains can be realised more quickly through other narrower, much more specific agreements”.

To illustrate this point, Alexander visited Taiwan last week (29-30 June) to participate in the 27th round of bilateral trade talks, which were first held in 1991. While in Taiwan, Alexander witnessed the signing of new Enhanced Trade Partnership (ETP) pillars on Investment, Digital Trade, Energy and Net Zero. Alexander also confirmed plans to continue to work with Taiwan to identify ways to further develop the ETP in the Autumn.

On 30 June, Alexander met Taiwanese President Lai Ching-te, with Lai posting: “It’s been a pleasure to see our ties grow through collaboration in energy, tech & education I’m confident we will continue to help drive Indo-Pacific prosperity”.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, China features prominently in the Trade Strategy – acknowledging China as the UK’s fifth-largest trading partner, and positions engagement with China as vital for achieving growth – particularly in services, which are currently underrepresented in UK exports to China. It restates the Government’s commits to a long-term, strategic approach, including reopening political dialogue on trade through the long-awaited UK-China Joint Economic and Trade Commission.

This is balanced against areas where there are long-standing concerns: “There are many areas where we are happy to let trade flourish, but there are areas where we rightly need to exercise caution and ensure that we focus on resilient growth. We acknowledge there are sensitive sectors needing careful consideration, to ensure that we do not compromise our national security. We will not hesitate to protect the UK’s interests where we need to”.

The Trade Strategy strengthens the UK’s ability to defend itself in the global trading system - with Alexander explaining: “We will promote what we can and protect what we must… We will expand and sharpen our range of trade defence tools in our toolbox to be able to respond to unfair competition”.

Expanding on this, Chapter 5 ‘Secure and Resilient Trade’, is probably the most interesting section of the Strategy from a UK-China perspective. Even though China is not mentioned once by name in this Chapter, its presence looms large over all of the measures discussed. Some points worth noting:

The Government is “launching a new ‘Supply Chain Centre’ based in the Department for Business and Trade, that will lead government’s work, in tandem with business, to build the resilience of the supply chains critical to the UK’s security and prosperity, helping to secure our ability to withstand future disruptions”.

There are also plans afoot to “introduce legislation to expand our powers to respond to unfair trade practices, and guard against global turbulence in critical sectors, such as steel”. In the case of steel, in particular, it is unclear whether these new powers might be used against China, the US, or both.

Interestingly, it seems the Government may be planning to develop its own ‘Anti-Coercion Instrument’ – presumably based on the EU’s version: “We will seek views on the potential for new powers to respond to deliberate economic pressure against the UK, to better protect growth and security against a burgeoning range of harms and threats”.

There was also a pointed reference to long-standing concerns over China’s economic model and extensive use of industrial subsidies: “We will continue to utilise bilateral, plurilateral or multilateral opportunities to improve subsidy transparency and the rule framework [sic] on market distorting practices, including such practices by state-owned enterprises”.

The Government is also looking to “introduce legislation to adjust the Trade Remedy Authority’s policy guidance and operating framework, enabling it to adopt a more assertive approach on issues like imports from countries with unfair market distortions”. The assumption here would be that this would result in more frequent use of trade remedies against Chinese imports.

Curiously, the Strategy also sets out plans to “establish an Economic Security Advisory Service based in the Department for Business and Trade that will streamline the Government’s approach to partnering with business on economic security issues… The service will collaborate closely with other institutions focused on security, including National Protective Security Authority, the National Cyber Security Centre, as well as the new Supply Chain Centre and the Geopolitical Impact Unit”. This sounds not entirely dissimilar to the “diplomatic advisory hub” announced by the Foreign Secretary back in March.

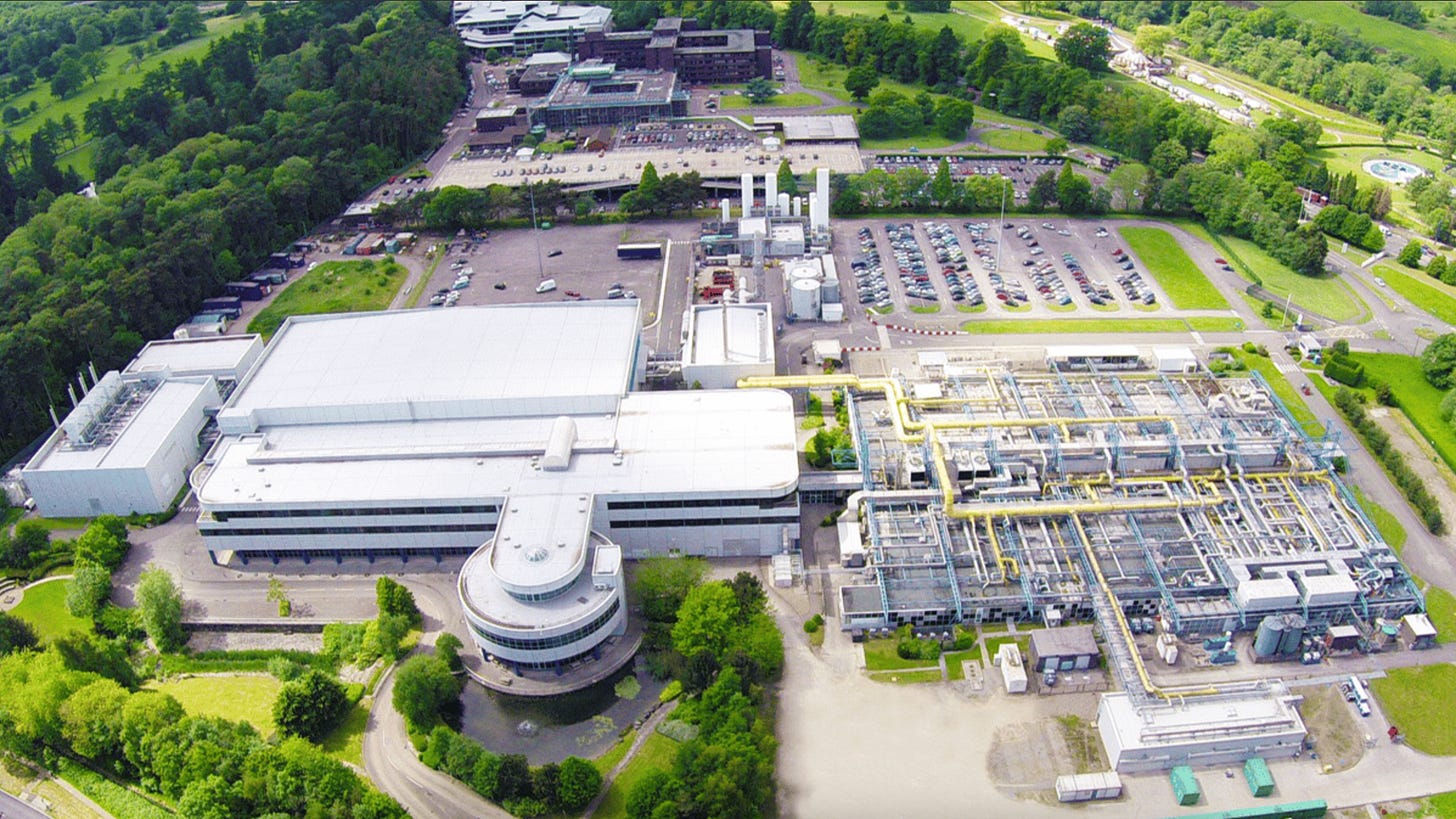

It was notable that both case studies in this Chapter were directly or indirectly linked to China. The first highlighted Vishay Intertechnology’s investment in Newport Wafer Fab after the previous Chinese owners were forced to divest their stake in 2022, under the newly-introduced National Security and Investment Act. The second case study profiles the UK steel industry, which has been in the headlines in recent weeks after the UK Government took control of the Chinese-owned British Steel. The Strategy highlights the launch of a new Call for Evidence which seeks “views in shaping the UK’s future trade approach to steel”, which has a deadline of 7 August 2025.

In the April issue of our paid subscriber-exclusive product, The Rebrief, we explained the strategic significance of the UK’s membership of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP): “Without US or Chinese dominance, the UK has a rare opportunity to shape the future direction of global trade alongside like-minded middle powers rather than being forced to choose between rival superpowers”.

This prediction appears to have been borne-out in the Trade Strategy with a meaty section dedicated to how CPTPP might evolve in the years ahead:

“CPTPP provides a platform for a diverse group of major economies to come together and discuss how to deepen and extend the reach of high standards trade. That means it is a platform that is more important than ever in the current global context… we will work with CPTPP Members and partners beyond the group to pursue… the expeditious expansion of CPTPP to additional economies, using the accession process to bring other economies into the orbit of high standards trade rules [and] use CPTPP as a platform to support the wider multilateral and plurilateral system, and to encourage deeper trading relationships between countries and groupings committed to liberal rules-based trade [and] work towards dialogues with the EU and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)… to further facilitate and liberalise global trade”.

China formally submitted its application to join CPTPP on 16 September 2021. Taiwan, officially as “The Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu (TPKM)”, quickly followed with its own application on 22 September [The Editor: As if to highlight the growing diversity and breadth of CPTPP’s membership, in 2023, Ukraine submitted its formal request to join CPTPP. The most recent applicant is Indonesia, who officially applied in September 2024, and have recently also joined the BRICS grouping].

The National Security Strategy

The focus on economic security in the Trade Strategy complemented the new National Security Strategy (NSS), which was published a couple of days earlier, on 24 June.

The stated purpose of the NSS was to “identify the main challenges we face as a nation in an era of radical uncertainty; and to set out a new Strategic Framework in response, covering all aspects of national security and international policy”.

The NSS represents “a hardening and a sharpening of our approach to national security across all areas of policy”. It paints a sobering picture of the range of threats facing the country, up-to-and-including the possibility of war: “adversaries are laying the foundations for future conflict, positioning themselves to move quickly to cause major disruption to our energy and or supply chains, to deter us from standing up to their aggression. For the first time in many years, we have to actively prepare for the possibility of the UK homeland coming under direct threat, potentially in a wartime scenario”.

On China, the NSS sets out that “Consistency is essential in approaching the geostrategic challenge posed by China”, citing the “importance of diplomacy in approaching this challenge”.

Diplomacy aside, the Government also will no doubt be hoping the Strategic Defence Review and the aforementioned Industrial Strategy will help the UK to compete in areas which are critical for national security:

“Authoritarian states are putting in place multi-year plans to out-compete liberal democracies in every domain, from military modernisation to science and technology development, from their economic models to the information space… the challenge of competition from China – which ranges from military modernisation to an assertion of state power that encompasses economic, industrial, science and technology policy – has potentially huge consequences for the lives of British citizens”.

Among the consequences of this new era of ‘great power competition’ is the “willingness of adversaries and competitors to work more closely together”:

“North Korea not only threatens its neighbours in Asia through ballistic missile testing; it has sent thousands of troops to support Russia’s illegal war in Ukraine, directly confronting those seeking to preserve European security. Iran has delivered missiles and drones to Russia while China has helped Putin maintain his defence industrial base”.

In a recent interview with the New York Times, NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte explained the significance of this coordination between adversaries: “There’s an increasing realisation, and let’s not be naïve about this: If Xi Jinping would attack Taiwan, he would first make sure that he makes a call to his very junior partner in all of this, Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin, residing in Moscow, and telling him, ‘Hey, I’m going to do this, and I need you to to keep them busy in Europe by attacking NATO territory’. That is most likely the way this will progress”.

Continuing the US’ longstanding policy of “strategic ambiguity” over Taiwan, on Wednesday (9 July), CNN published audio of President Trump speaking a fund-raising event in 2024: “I’m with President Xi of China… I said you know ‘if you go into Taiwan I’m going to bomb the sh*t out of Beijing’. He thought I was crazy… I said ‘I have no choice. I got to bomb you’”.

Last week, SCMP exclusively reported that China had said the quiet part out loud: “Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi told the European Union’s [High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Kaja Kallas] on Wednesday (2 July) that Beijing did not want to see a Russian loss in Ukraine because it feared the United States would then shift its whole focus to Beijing… Some EU officials involved were surprised by the frankness of Wang’s remarks… Any appearance of a charm offensive is seen to have evaporated”.

As we have explored previously, Wang’s brittle brand of proto-Wolf Warrior diplomacy continues to undermine prospects for closer alignment with Europe – despite the US’ best efforts to sever transatlantic ties. While more skilled and imaginative diplomats might see strategic openings in the current US-EU tensions, Wang’s value appears to lie in his loyalty and ideological steadfastness. His dismissiveness and inflexibility may frustrate Western partners, but, in the Chinese system, that’s clearly a feature, not a bug.

Suffice to say, this does not seem to bode well for the forthcoming EU-China Summit, due to be held in Beijing and Hefei on 24-25 July [The Editor: We will be covering the highlights – or lowlights – from that summit in the July issue of The Rebrief].

Elsewhere, the NSS highlights the “centrality of the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait to global trade and supply chains” and the “particular risk of escalation around Taiwan”. It outlines the UK’s position: “the Taiwan issue should be resolved peacefully by the people on both sides of the Strait through constructive dialogue, without the threat or use of force or coercion. We do not support any unilateral attempts to change the status quo”. The NSS also commits to continuing “strengthen and grow [UK-Taiwan] ties in a wide range of areas, underpinned by shared democratic values".

Last month (18 June), the HMS Spey passed through the Taiwan Strait, as part of a planned deployment to the region. This was the first such patrol by a British naval vessel in four years. China described the passage as an “intentional provocation that disrupts the situation and undermines peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait”, adding it would “resolutely counter all threats and provocations”.

It seems China were not the only ones who were unhappy about the deployment. On Tuesday (8 July), Politico published a remarkable anecdote about US Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Elbridge Colby: “When the British defense team came to the Pentagon in June and spoke about the UK’s decision to send an aircraft carrier to Asia on a routine deployment, Colby interjected with a brusque comment. ‘He basically asked them, ‘Is it too late to call it back?’’ said the person familiar with Trump administration dynamics. ‘Because we don’t want you there’. A second person familiar with the meeting confirmed this account. The British team on the other side of the table ‘were just shocked’, the first person added. ‘He was basically saying ‘you have no business being in the Indo-Pacific’”.

Finally, the NSS articulated, at a high-level, the main conclusions of the long-awaited China Audit:

“The process of auditing our interests with respect to China, in line with the government’s manifesto commitment, is now complete. This work underscores the need for direct and high-level engagement and pragmatic cooperation where it is in our national interest… In a more volatile world, we need to reduce the risks of misunderstanding and poor communication that have characterised the relationship in recent years. China’s global role makes it increasingly consequential in tackling the biggest global challenges, from climate change to global health to financial stability. We will seek a trade and investment relationship that supports secure and resilient growth and boosts the UK economy. Yet there are several major areas, such as human rights and cyber security, where there are stark differences and where continued tension is likely. Instances of China’s espionage, interference in our democracy and the undermining of our economic security have increased in recent years. Our national security response will therefore continue to be threat-driven, bolstering our defences and responding with strong counter-measures. We will continue to protect the Hong Kong community in the UK and others from transnational repression”.

So far, so generic - the section continues:

“The China Audit therefore recommends an increase in China capabilities across the national security system to strengthen ability to engage, as well as our resilience and readiness on the basis of deeper knowledge and training. That includes creating the basis for a reciprocal and balanced economic relationship, by providing guidance to those in the private or higher education sectors for which China is an important partner. To ensure that the public, businesses, academia and partners understand our approach, and have the right guidance to help them make safe decisions, we will bring together existing guidance on China in a new gov.uk hub and continue to develop comprehensive guidance relevant to engagement with China”.

Little did we know at the time, these paragraphs would represent the only substantive written record we have of the outcomes from the China Audit.

A few other points of note:

The NSS describes the UK’s Diplomatic Service as “a unique asset [with] deep expertise and knowledge, enabling the UK to project influence, protect its interests, and support British citizens”. A few sentences later the NSS talks of “reforming the [Foreign Office’s] workforce” to become “smaller, more agile… with a higher proportion of staff overseas”, as well as “a new College of British Diplomacy”. Talk about mixed messages.

Awkwardly buried in the middle of the same section, there seems to be an oblique reference to the work of MI6’s field operatives: “This [overseas network] supports upstream interventions to counter threats before they reach our shores, defending the UK’s security against hybrid threats, and underpinning the UK’s ability to act as a credible global partner”. This section continues that the Government will be making a “£290 million investment in world class capabilities”. What will this investment be in, and what capabilities is it referring to? If they told you, they’d probably have to kill you, so best not ask.

Building on the increased emphasis on mini-lateralism and plurilateralism set out in the Trade Strategy, the NSS explains the UK will: “Sharpen our diplomatic focus on countries that are geographically dispersed but economically vibrant and technologically advanced – particularly those (from Canada through the Gulf States, to India, Indonesia, Singapore, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand) who are interested in cooperation on trade and security, sit outside large regulatory blocs and share a similar interest in shaping international norms to mitigate and manage the effects of great power competition”.

Taken together, these three new strategies – alongside the Strategic Defence Review – offer the clearest articulation of the UK’s overarching foreign and security policy priorities, and by extension its strategy, in well over a decade.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of the UK’s approach to China.

The China Audit

On 24 June, a few hours after the National Security Strategy had been launched, the Foreign Secretary David Lammy stood up in the House of Commons to provide a statement on the outcomes of the UK’s much-anticipated China Audit.

The statement, barely ten minutes long, provided little-to-no detail on what had actually been achieved by officials in his department in the last twelve months.

“This Government conducted an audit of our most complex bilateral relationship to deliver a long-term strategy, moving beyond cheap rhetoric to a data-driven, cross-Government approach. I would like to thank the hundreds who contributed to it, including Honourable Members, of course, and experts, businesses, diaspora communities, devolved Governments and close allies. The audit is less a single act than an ongoing exercise that will continue to guide the UK’s approach to China”.

Those still expecting anything of substance to be shared were quickly disappointed with the Foreign Secretary’s next lines: “Honourable Members will understand that much of the audit was conducted at a high classification and that most of the detail is not disclosable without damaging our national interests. I am therefore providing a broad summary of its recommendations today in a manner consistent with that of our Five Eyes partners”. This is questionable, to say the least.

It is telling that the Foreign Secretary chose to compare the UK’s approach to “Five Eyes partners”, rather than European neighbours. In July 2023, Germany published its first comprehensive ‘Strategy on China’. This detailed 64-page document outlines Germany’s approach to relations with China, categorising the country as simultaneously a “partner – competitor – systemic rival”. It signals a strategic shift from its traditionally business-focused engagement to a more risk- and security-conscious stance, aligned with broader EU policies.

It is also worth noting that the UK’s foremost “Five Eyes partner”, the US, has also published various formal, written strategies that explicitly address China in recent years:

In May 2020, the US set out their ‘Strategic Approach to the People’s Republic of China’.

In February 2023, the State Department published their ‘Integrated Country Strategy’ for China.

The Department of Defense also publishes a comprehensive annual report on ‘Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China’.

Suffice to say, the UK currently has no current equivalent to these documents. The Foreign Secretary continued:

“On security, the audit described a full spectrum of threats… Honourable Members will again recognise that disclosing the detail of the responses to those threats would undermine their effectiveness. However, I can confirm that following the audit we are investing £600 million in our intelligence services; updating our state threats legislation following Jonathan Hall’s review; strengthening our response to transnational repression; introducing training for police and launching more online guidance to support victims; launching, as announced in the industrial strategy, a 12-week consultation on updating the definitions covering the 17 sensitive areas under the National Security and Investment Act 2021; and working bilaterally with China to enhance intelligence flows related to illicit finance specifically, organised immigration crime and scam centres, using new National Crime Agency capabilities”.

Most of these measures had already been announced prior to the Foreign Secretary’s statement. The Foreign Secretary then moved on to talk about opportunities China presents for the UK:

“China will continue to play a vital role in supporting the UK’s secure growth, but over the past decade we have not had the structures either to take the opportunities or to protect us from the risks that those deep links demand. Businesses have told us time and again that they have lacked senior political engagement and adequate Government guidance… We have already begun to develop new structures, including regular Economic and Financial Dialogues with my Right Honourable Friend the Chancellor, setting us on course to unlock £1 billion of economic value for the UK economy and positioning the UK’s world-leading financial sector to reflect China’s importance to the global economy; Joint Economic and Trade Commissions; and Joint Commission meetings on science”.

Again, none of these dialogues are new, and the fact the Foreign Secretary was highlighting the lack “adequate Government guidance” while refusing to publish any substantive detail on outcomes from the China Audit was a rather brave decision, to say the least.

The only section of the statement which contained anything that could be considered genuinely new or novel came right at the end:

“The audit showed that under the last Government there was a profound lack of confidence in how to deal with China and a profound lack of knowledge regarding China’s culture, history and—most importantly—language. Over the past year, I have found that far too few mandarins speak Mandarin. We are already taking action to address that by introducing a new China Fast Stream in the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, creating an FCDO global China network and training over 1,000 civil servants on China policy in the past year. Enhancing those capabilities still further will be a core focus for the £290 million FCDO transformation fund announced in the National Security Strategy by my Right Honourable Friend the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster a short time ago. The new strategy, which proceeds from the audit, will ensure that the Government examine the full spectrum of interests in their decision-making processes and deliver the consistent approach that was so sorely lacking”.

The lack of specificity and detail over these proposals is concerning – it is unclear why the new “China Fast Stream” will be limited to the Foreign Office, given the Audit makes abundantly clear much of the substantive engagement with China is led by other government departments - including the Cabinet Office, HM Treasury, Department for Business and Trade, Department for Energy Security and Net Zero and Department for Science, Innovation and Technology - to name just a few.

No detail is provided on what the “FCDO global China network” consists of and the quoted “1,000 civil servants” trained on “China policy” – whatever this means – is at best, questionable; at worst, actively misleading [The Editor: It certainly appeared to mislead some members of the Foreign Affairs Committee, as we will see below].

The lack of detail in these announcements gives the impression these ideas that were thrown together in a matter of days or weeks, rather than carefully developed through months of painstaking work.

There is also no small irony in decrying the “profound lack of confidence” from the previous government in setting out how it intended to deal with China while, in the same breath, failing to set out how the current Government intends to deal with China.

This truly was Schrödinger's China Audit – an audit that may or may not have happened, and may or may not be implemented. Without the detail, policy substance or any hard metrics, we will simply never know – which is, presumably, the idea.

The Foreign Affairs Committee Response

If nothing else, the Foreign Secretary’s statement seems to have succeeded in sparking life into the otherwise moribund Foreign Affairs Committee. On Tuesday (8 July) Committee Chair, Dame Emily Thornberry, released a suitably punchy statement on the outcomes of the China Audit:

“We were promised a ‘full and comprehensive audit on the breadth of the UK's relationship with China’. Instead, we were given three paragraphs on page 39 of the National Security Strategy. Parliament and the public have been left with more questions than answers. In the absence of a published China audit, we are placing the first tranche of written evidence we received as part of our inquiry into the UK's China audit into the public domain today (8 July). At the moment we are operating in the dark. We understand the need for sensitive matters to be kept classified, but the Government must get the balance right. Presumably there isn't just an audit, there is a strategy coming from that. We haven't seen the audit and we don't know what's in the strategy - which should apply to government, local government, business, universities and particularly the technology sector. Surely, we all need to know this so that we can act together in our approach towards China. The Government says the purpose of the audit was to ensure that we have a consistent attitude towards - how can we do that if we don't know what it is?”.

The same day, Dame Emily had a chance to raise her concerns directly with the Foreign Office’s new(ish) Permanent Under Secretary, Sir Olly Robbins – who was making his first appearance before the Foreign Affairs Committee. Robbins also accompanied the Foreign Secretary to a second session with the Committee a few hours later.

The aforementioned of “1,000 civil servants” was repeatedly referenced in both sessions as the number of Mandarin speakers the FCDO was aiming to train. As we explained above, this was simply the number of officials the Foreign Office claimed to have trained on “China policy” over the past year. Yet, for reasons unknown, neither the Foreign Secretary nor Sir Olly chose to correct this significant misunderstanding when it arose in Committee.

However many Mandarin-speakers the Foreign Office is actually hoping to train, it will be starting from a very low base. Sir Olly seemed to believe there were “around 70” Chinese speakers in the Foreign Office who had attained the “highest level… of total business fluency”. By the time of the Foreign Secretary’s appearance, this estimate had increased to “70 or 80” attaining the “highest proficiency”.

In February, The Spectator reported that, according to a recent Freedom of Information request, only 22 Diplomats had attained C1 level – a figure that had halved in the last decade. It is also worth noting that C1-level Mandarin – broadly equivalent to HSK Level 5 – is a long way from “total business fluency”, as we’ve highlighted previously. The number of Foreign Office staff who can speak Mandarin to C2-level – the actual “highest proficiency” – is believed to be as few as five.

During his session with the Committee, Sir Olly shed light on the “change programme” currently underway in the Foreign Office – named “FCDO 2030” – which will result in the department becoming “significant smaller over the course of the next three to four years” with 15%-25% cuts to total headcount expected by 2029. The Permanent Under Secretary explained there would be “a bias towards having a larger proportion of our workforce overseas at the end of the Parliament than we have today”.

On the subject of the China Audit, Sir Olly was less forthcoming, much to the annoyance of the Dame Emily: “If we, as a nation, need to look again at our [relationship] with China… how on earth do we do that if there is a secret audit with a secret strategy that we’re not allowed to know about?”. There was something rather uncomfortable about watching an unelected official telling elected Parliamentarians they could not see information they might reasonably expect to be able to see to allow the Committee to fulfil its sole function – scrutinising the work of the government and holding it to account.

During the Foreign Secretary’s two-hour-long appearance there were only three questions on China – none of which shed any further light on the Government’s approach. On the question of how many “China Fast Streamers” there would be and when the first cohort would be graduating, the Foreign Secretary seemed unsure, and agreed to write to the Committee at a later date. The Foreign Secretary also confirmed nothing more of the China Audit, or China Strategy, could or would be shared.

Think Tanks and the Media Response

It seems Dame Emily and Foreign Affairs Committee members are not alone in their frustrations over the China Audit – The Times’ writes:

“I was disappointed, but not surprised, to hear about the unceremonious end to the dragged-out saga of the China audit. All we know of its findings, after a year of cross-governmental work, is two paragraphs in the national security strategy and a ten-minute statement by the foreign secretary in the Commons… it’s a sorry shadow of what the China audit could, and should, have been. It was an opportunity to give an authoritative and comprehensive answer to the pressing question of: how can British interests be best served while co-existing with China?... The audit might also have started a conversation about how the UK could do better domestically… All of this thinking may have been done behind Whitehall’s doors, but a secret China policy is not a good China policy. Businesses wanting to know if they can co-operate or take investment in certain areas, or universities questioning research collaboration, are left none the wiser. They look at the cautionary tale of BT, which has spent £500 million on ripping out Huawei kit from its networks after the government’s dithering and eventual ban. Without clear guidance, we’re doomed to repeat that pattern… So why did such a crucial document get pulled, and seemingly at the last minute? If it was a question of sensitive information, it beggars belief that a non-classified version couldn’t be released… But the cynic in me also wonders if it isn’t because the task is just too difficult. There is a shocking lack of China expertise in Whitehall (even in the Foreign Office, where the number of fluent Mandarin speakers has halved in less than a decade). Lammy recognised the need to improve the government’s China literacy in his statement, but I understand that the amount of money allotted to that goal is a measly £5 million” [The Editor: It’s unlikely to be even that].

Despite concerns over the number of mandarins that speak Mandarin, Chatham House’s Dr William Matthews believes the problems may be rather closer to home for the Foreign Secretary, writing:

“Judging by the Parliamentary footage, this debate on the first serious attempt by a UK government to put forward a systematic approach to China drew only a few dozen politicians… So why the indifference? At root, this is attributable to a lack of baseline knowledge and a persistent belief that there is something about China which makes it inherently too complex to engage with if one is not an expert. This creates fertile ground for polarised and uninformed debate which falls short of the level of rigour Britain needs if it is to adapt to a world of increasing Chinese influence. For Parliament to effectively foster scrutiny of China policy and hold the Government to account, it requires informed engagement founded on bipartisan recognition of the magnitude of the challenges Beijing presents. What Westminster often gets right is its discussion of China’s troubling human rights record... But this knowledge appears to be isolated from wider consideration of China’s geopolitical role and power relative to the UK. The result is an entirely unworkable position that calls for no engagement with the world’s second-largest economy purely on principle, or which relies on unrealistic faith in Britain’s ability to influence China’s domestic affairs. There are choices to be made about how and when to engage with Beijing. But without publication of at least some concrete findings and the methods of the Government’s China audit, those choices could be misguided. The most fleshed-out recommendation Lammy announced was an increase in funding for improving China expertise. Some of that ought to be spent in Parliament”.

The most obvious consequence of failing to publish anything from the China Audit is that it invites people to project their own assumptions onto the outcome reinforcing pre-existing views rather than clarifying the Government’s actual conclusions [The Editor: Something that we freely admit we are doing right now] . This undermines the entire purpose of having conducted the review in the first place.

A prime example of this came from former BBC journalist Paul Mason, currently a Aneurin Bevan Associate Fellow in Defence and Resilience at the Council on Geostrategy, who writes: “If someone commissions an audit and then suppresses the results, the assumption has to be that they have discovered something bad. Labour began its cross-Whitehall ‘China Audit’ a year ago, but after its conclusion this week we are none the wiser about the biggest question facing us in the 21st century”.

Perhaps we shouldn’t have been surprised that the long wait for the China Audit ended this way. Back in March, we highlighted “the Foreign Office’s track record suggests that expectations [for the China Audit] should be tempered; without a fundamental shift in approach, this risks becoming yet another missed opportunity”. Unfortunately, it seems that we were correct in this assessment.

The clearest takeaway from this sorry exercise is that the greatest obstacle to a coherent UK policy on China remains the Foreign Office itself. Once a bastion of diplomatic expertise, it has been systematically hollowed out – lacking not only the personnel, but the intellectual self-confidence to even begin to articulate a clear, credible public position. Paralysed by risk aversion and institutional drift, it now struggles to perform even the basic functions of foreign policy – hiding behind security classifications and vague allusions to national security. The China Audit debacle exposes this rot more than it addresses any strategic challenge: not because of what it reveals about China, but because of what it reveals about us.

In order to see just how far the Foreign Office has fallen, we only need to look back to the last Labour Government to how it might have been possible to do things differently, if not for its current “profound lack of confidence”.

The UK and China: A Framework for Engagement

On 22 January 2009, the-then Foreign Secretary David Miliband - older brother of the current Energy Secretary - was in Manchester to launch the first, and last, UK government document to set out the an approach for the UK's relationship with China.

Entitled ‘The UK and China: A framework for engagement’, the document has been largely scrubbed from the Government webpages – never to be revisited or updated in the following sixteen-and-a-half years.

Written in the midst of the Global Financial Crisis, in the foreword, the-then Prime Minister Gordon Brown called on China to: “play a full role, in partnership with us… to restore confidence, growth and jobs and make real progress towards creating an open, flexible and robust global economy”.

China subsequently played a critical role in pulling the global economy out of recession, launching a massive domestic stimulus package and sustaining high levels of infrastructure investment, bolstering global demand for commodities and exports.

Much like the China Audit, vague commitments were made on China expertise that were clearly never fulfilled: “If we are to make the most of our relationship with China, we need to understand China better, through our schools, universities, cultural institutions, our businesses and in Government. I am determined to do just that”.

The three pillars of the framework were not entirely disimilar to the current approach – at least, in so far as it has been articulated:

“Getting the best for the UK from China’s growth: This is about encouraging China to see the UK as a global hub, and boosting our business, educational, scientific and cultural gains from the bilateral relationship. It’s also about ensuring the UK has the right domestic policies in place to benefit from China’s growth.

Fostering China’s emergence as a responsible global player: This is about encouraging an approach of responsible sovereignty on international and global issues, from proliferation and international security to sustainable development and climate change. It’s also about helping China to define its interests increasingly broadly.

Promoting sustainable development, modernisation and internal reform in China: This is about influencing China’s evolving domestic policies, helping China manage the risks of its rapid development and, over time, narrowing differences between us. Greater respect for human rights is crucial to this”.

Some sections could very easily have been cut-and-paste into the China Audit and few would have even noticed:

“Working towards the outcomes we want will require patience, persistence and effective partnership, being candid where we disagree but ensuring the relationship remains characterised by co-operation, not confrontation. Building a progressive, comprehensive relationship with China will be a major priority in the years ahead”.

The framework listed over forty specific objectives for the bilateral relationship – the results of which have been mixed, to say the least. While limited progress was made in “Getting the best for the UK from China’s growth”, it is arguable that most progress was made in “Fostering China’s emergence as a responsible global player”. Even then, the final objective in this pillar is loaded with ominous foreshadowing: “China co-operates fully on global health issues with the World Health Organisation, complying with best practice on avian influenza, and other health security issues” [The Editor: In 2011, Xi Jinping’s wife – Peng Liyuan – was appointed WHO’s Goodwill Ambassador for Tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS. A decade later, in 2021, Brown became a World Health Organisation Goodwill Ambassador for Global Health Financing].

Perhaps unsurprisingly, least progress was made against the third and final pillar – which focused on “sustainable development, modernisation and internal reform” to China’s domestic political and economic system.

Like many post-Cold War illusions, the widespread assumption that China would liberalise through integration – becoming ‘more like us’ – revealed more about Western projection than Chinese intent.

Multinationals, eyeing both a vast consumer market and the promise of cheap labour, were among the loudest champions of China’s WTO accession – viewing deepening engagement as a vehicle for offshoring, cost-cutting, and profit maximisation.

Western politicians and policymakers, in turn, mistook economic reforms for ideological malleability, reading too much into signals of legal or governance modernisation. Yet for the CCP, such reforms were merely a means to an end – a pragmatic necessity, not steps toward convergence.

Despite this, there were perhaps moments, particularly in the 1990s and early 2000s, when limited political experimentation appeared possible. But the 2008 Global Financial Crisis marked a turning point – reinforcing the CCP’s scepticism of Western models. Any lingering hopes for political reform were definitively snuffed out with Xi’s rise to power in 2012.

The framework’s calls for China to “[strengthen] its social welfare provision, lowering savings rates and boosting domestic demand” and “[develop a] stronger rule of law and more independent judiciary” seem as dim and distant a prospect today as they probably were then, with the benefit of hindsight.

Similarly, calls for “meaningful autonomy for Tibet” led nowhere, and the ship has long-since sailed on hopes for Hong Kong’s democratic future. The framework called for “Significant reform for the 2012 elections in Hong Kong, to prepare the way for the election of HK’s Chief Executive by universal suffrage in 2017 and fully democratic Legislative Council by 2020”. The National Security Law in Hong Kong was drafted by mainland Chinese authorities and introduced on 30 June 2020, without local legislative consultation.

While it’s tempting to dismiss some of these earlier visions for the UK-China relationship as overly optimistic, it’s worth recognising the areas where genuine progress was made – and the aspects of the framework that have, perhaps unexpectedly, endured. The framework’s most enduring lesson, however, is the necessity of approaching China as it is, not as we might wish or imagine it to be.

More importantly, we should recognise the value in a document like this being published at all. At the time, the Chinese economy was roughly double the size of the UK economy in nominal terms. Today, China’s economy is roughly five times the size of the UK’s. Total bilateral trade is around 40% higher today in real terms than 2009, even after accounting for inflation. And yet, despite China’s ever-growing importance to the UK, it is concerning that the Foreign Office does not seem to deem it necessary to produce a similar framework to guide the UK’s engagement today.

In the framework’s foreword, the Foreign Secretary proudly declares: “We have never before set out publicly our policy on China in this way and this document is intended to begin a broader conversation”. Unfortunately, barely eighteen months after publication of the framework, Labour lost the General Election – relegating this document to a forgotten relic of Gordon Brown’s turbulent and short-lived Premiership.

The UK’s “broader conversation” on China sadly never happened and, judging by the fate of the China Audit, it seems increasingly likely it probably never will.

I’m Going To Tell Daddy On You

In one of the more bizarre developments of recent weeks, NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte referred to President Trump as “Daddy” at the NATO Summit in the Hague last month (24-25 June).

At the Summit, members agreed to invest 5% of GDP in defence by 2035 – including 3.5% of GDP on core defence requirements and 1.5% on defence- and security-related investments. One imagines it will be quite a stretch for many NATO members – particularly as nine NATO members failed to even hit 2% in 2024.

For their part, the White House seems to have embraced the new “Daddy” nickname publishing a video to mark President Trump’s triumphant return from Europe. Never one to miss a money-making opportunity, Trump’s fund-raising committee have also started selling “Daddy” T-shirts.

On Monday (7 July), President Trump extended the deadline for the imposition of “reciprocal” tariffs from 9 July to 1 August. According to Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent: “It’s not a new deadline. We are saying ‘this is when it’s happening. If you want to speed things up, have at it. If you want to go back to the old rate, that’s your choice’”.

Revised tariffs were announced for 14 countries including Indonesia (32%, no change), Japan (25%, +1%), South Africa (30%, no change) and South Korea (25%, no change). Of the remaining countries, the majority saw headline tariff rates reduced. Trump described the trade deficits with Japan, South Korea and others “a major threat to our economy and indeed our national security”. New tariffs on further a six countries were announced yesterday (9 July). Expect this pattern to continue for the rest of the month.

At the time of writing, the US has only struck trade deals with three countries – UK, China and Vietnam. On Monday, President Trump told reporters the US was “very close” to striking a deal with India.

The same day, the BRICS Summit (6-7 July) concluded in Rio de Janeiro. Premier Li Qiang attended in place of President Xi – the first time the Chinese President has missed a BRICS Summit, amid rumours of health problems.

BRICS Members published a Joint Declaration, which criticised: “the proliferation of trade-restrictive actions… We voice serious concerns about the rise of unilateral tariff and non-tariff measures which distort trade and are inconsistent with WTO rules… We condemn the imposition of unilateral coercive measures that are contrary to international law… We call for the elimination of such unlawful measures”.

In response, President Trump lashed out against the grouping, posting: “Any Country aligning themselves with the Anti-American policies of BRICS, will be charged an ADDITIONAL 10% Tariff. There will be no exceptions to this policy”. Elsewhere, Indonesia was formally welcomed as a new BRICS member in the Declaration, as the first from South East Asia.

Host of the Summit, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva criticized NATO's decision to increase military spending, highlighting the world was already experiencing the highest number of conflicts since World War II, fearing this move would fuel a global arms race – leading to ever-greater instability.

Yesterday (9 July), in a letter to Lula, Trump threatened new 50% tariffs on Brazil, in part due to the treatment of former President, Jair Bolsonaro – currently on trial for an attempted coup – which the US President described as “a Witch Hunt that should end IMMEDIATELY” and “an international disgrace”. Trump signed off the letter in typically flamboyant fashion: “You will never be disappointed with the United States of America”. The US currently has a trade surplus with Brazil.

Amid reports that the Government is finally planning to give the green light to the new Chinese Embassy project at Royal Mint Court, the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China’s “I’m going to tell Daddy on you” campaign – as we have now dubbed it, given recent events – continues undeterred.

As we’ve noted previously, the campaign appears to rely on enlisting various US figures and institutions to weigh in on a case they’re only distantly connected to and in which they have limited knowledge or real stakes.

The flawed underlying assumption is that vague expressions of disapproval from Washington – frequently attributed to anonymous officials – will exert enough pressure to bring the UK into line, as though it were an errant child being told on by an exasperated sibling hoping to attract the attention of a distant and disengaged parent.

The Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) are the latest US-based organisation to wade in on the issue. On 13 June, CSIS published a piece by a 24-year-old Research Assistant entitled ‘Is China’s New London ‘Super Embassy’ a Risk to National Security?’.

While the piece provides more detail than many similar pieces in the mainstream media, it ultimately boils down to the same IPAC lobbying points – specifically “the site’s proximity to sensitive communication lines and fiber-optic cables used in London’s internet network” – with little new information of note.

Despite the author’s obvious lack of first-hand knowledge of the site, the piece confidently asserts the project will “pose a significant national security risk to the United Kingdom [and] provide Chinese intelligence services with a myriad of espionage opportunities [which will] jeopardise intelligence sharing with the United States and the Five Eyes alliance”.

Amid the range of variously wild and speculative claims, the author suggests “Part of the proposed Embassy House faces directly northwest, which may provide unobstructed views of 30 St Mary Axe (The Gherkin) and other key buildings in London’s financial district”. For context, The Gherkin is one of the most visible and widely-recognised buildings in London. It is not immediately clear what relevance this has to UK national security.

The Gherkin is currently owned by Safra Group, run by Brazilian-Lebanese billionaire Joseph Safra. Prior to their 2014 purchase, Fosun International, a major Chinese conglomerate was rumoured to be one of the shortlisted bidders. Elsewhere in the City, the iconic Lloyd’s Building has been owned by Chinese insurer Ping An since 2013. 20 Fenchurch Street – more commonly known as ‘The Walkie Talkie’ is owned by LKK Health Products, part of Hong Kong-based food group Lee Kum Kee (李錦記), who purchased it in 2017 for £1.3 billion – at the time the UK’s biggest single-building property deal.

To give credit where credit is due, the CSIS piece does at least acknowledge the obvious quid pro quo, with the redevelopment of the British Embassy in Beijing [The Editor: Which we originally highlighted nearly a year ago]:

“At the very least, the United Kingdom could conditionally approve China’s planning permit… while simultaneously applying pressure on Beijing to approve the United Kingdom’s own stalled embassy renovation project in central Beijing. Because the United Kingdom already intends to fully demolish and rebuild its aging embassy in Beijing, it could take this opportunity to submit a new building proposal that includes multistory [sic] towers, an expanded underground parking lot, other underground facilities, and a tunnel”.

The piece even offers some tips for the UK’s security services: “The UK embassy in Beijing… is strategically located in Beijing’s Central Business District and within striking distance of the Daily-Tech Chaolai Data Center and the Beijing World Financial Center, both of which could prove useful for MI6”. Let’s just hope China doesn’t find out.

Three days ago, CSIS held a live event on the project, which was “made possible by general support to the Intelligence, National Security, and Technology Program”. One can only assume a donor requested the event - or made a donation specifically for this purpose - because absent such prompting, it is difficult to see why a think tank of CSIS’s stature, which is normally focused on serious geopolitical and security matters, would devote time to a matter so utterly trivial by comparison.

Like many of the UK’s foreign affairs think tanks, CSIS receives a significant portion of its funding from major defence contractors, including Northrop Grumman, Lockheed Martin, Boeing and Raytheon.

On 29 June, IPAC’s go-to client journalists at The i Paper published a new ‘exclusive’ featuring quotes from Leon Panetta, who was the US Director of the Central Intelligence Agency between 2009 and 2011. The 87-year-old Panetta is quoted as saying:

“The UK has to take whatever steps are necessary to make sure that China does not use the location of a new embassy in order to be able to access British intelligence, or US intelligence for that matter. The UK has to be very smart about this, look at what the potential areas are that China could exploit, and take steps to make sure that does not happen. We went through that here in the US with the Russian embassy, with the Chinese embassy… It was clear that we had to impose some very tough requirements on them so that we would not just give them free access to intelligence sources. The UK is just going to have to be very tough with China to make sure that any new embassy doesn’t become just an intelligence centre for them”.

Panetta’s quote is a case study in both stating the obvious, and using a lot of words to say very little. The accompanying article also provides a helpful graphic which shows how “tall buildings at Royal Mint Court could provide Chinese intelligence with unobstructed views of the City of London” – referring back to the same questionable claims highlighted in the CSIS piece.

A few weeks earlier, 80-year-old Sir Richard Dearlove, former Chief of the UK’s Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) had told the i Paper: “If there are cables under the site, they’re probably fibre optic telecommunications lines. If they go under the site, the Chinese with impunity… can link into them [and] listen to everything or collect anything and everything going down those communication chains… That is a real problem. What I’ve heard is it’s unlikely for that reason to be agreed” [The Editor: Sir Richard – who retired in 2004 – appears to be looking to establish himself on the UK’s China-sceptic rent-a-quote circuit, presumably in case the omnipresent Charles Parton ever happens to be busy].

On Sunday (6 July), the Daily Mail published their own ‘exclusive’, which quotes an anonymous “US security source”, claiming: “There will effectively be a student-style campus for [more than 200] spies in the heart of the City. And those spy dungeons are so deep that the sensitive cables are virtually at head height”.

Last month, the Royal Mint Court Residents’ Association launched a GoFundMe campaign to fund a legal challenge against the Government’s anticipated approval of the project.

At the time of writing, the campaign has raised over £20,000 towards their £100,000 target. Given the campaign’s chances of success, we can only hope they decide to donate this money to a worthy cause instead.

A Major Major Speech

On 26 June, former UK Prime Minister Sir John Major gave a speech at the Sir Edward Heath Annual Lecture at the historic Salisbury Cathedral.

The 800-year-old Cathedral contains one of oldest working clocks in the world, as well as one of the four surviving original copies of Magna Carta, however, in recent years Salisbury has become (in)famous for another reason.

On 4 March 2018, former Russian double-agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter, Yulia, were poisoned in Salisbury with a Novichok nerve agent. Two Russian men - Alexander Petrov and Ruslan Boshirov – were charged, in absentia, in connection with the poisoning.

Shortly after returning to Russia, Boshirov told RT (formerly Russia Today) the pair were in Salisbury to visit the Cathedral which is: “famous not just in Europe, but in the whole world. It’s famous for its 123-metre spire, it’s famous for its clock, the first one [of its kind] ever created in the world, which is still working”. Petrov continued: “Our friends had been suggesting for a long time that we visit this wonderful town”.

The Annual Lecture was named after Sir Edward Heath – the former Conservative Prime Minister (1970-1974) – who passed away in 2005, aged 89. Sir Edward – who lived at Arundells, a Grade II-listed house in Cathedral Close, Salisbury, from 1985 until his death – played an important and under-explored role in the development of UK-China ties.

During Sir Edward’s time as Prime Minister, the UK upgraded its diplomatic recognition of the People's Republic of China to full ambassadorial level in 1972, the same year as US President Richard Nixon’s historic visit to the country.

After leaving office, Sir Edward became an unofficial envoy between the UK and China. In 2014, the-then Chinese Ambassador to the UK, Liu Xiaoming gave speech at Arundells in his memory, entitled ‘The Memory of Friendship Never Fades’:

“To all of us in China who cherish his memory, Sir Edward is highly regarded as ‘an old friend of the Chinese people’. Sir Edward’s premiership oversaw the establishment of ambassadorial diplomatic relations between China and the UK in 1972. This launched a new era of relations between our two countries. Since 1974 Sir Edward visited China 26 times during the following 27 years. After the famous British scholar Dr Joseph Needham [The Editor: Subject of the 2009 Simon Winchester book ‘The Man Who Loved China’], he was the second British person to be awarded ‘People’s Friendship Envoy’. This is the highest honour of people-to-people diplomacy that China ever gives to a foreigner. Sir Edward was also the last foreign politician who had met the three Chinese leaders: Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping”.

For his part, Sir John Major was the first British Prime Minister to visit China following Margaret Thatcher’s visit in 1984. His September 1991 visit was a diplomatic effort to rebuild relations post-Tiananmen Square.

At the time, Sir John faced criticism as the first major western leader to visit the country after massacre two years earlier, which had made China an international pariah. Sir John was hosted in Beijing by Li Peng, nicknamed the “Butcher of Beijing”.

During his three-day visit, Sir John publicly challenging China’s leaders over religious freedom, freedom of speech, an uprising in Tibet, the detention of student demonstrators and the massacre itself. “The world has not forgotten the events of June 1989”, Sir John told a press conference in Beijing – taking 17 questions from the gathered journalists, nine of which were about human rights or the fight for democracy.

In Sir John’s speech in Salisbury, Russia featured prominently – as one might expect, given the venue – as did human rights and democratic values, particularly with respect to the US and China: